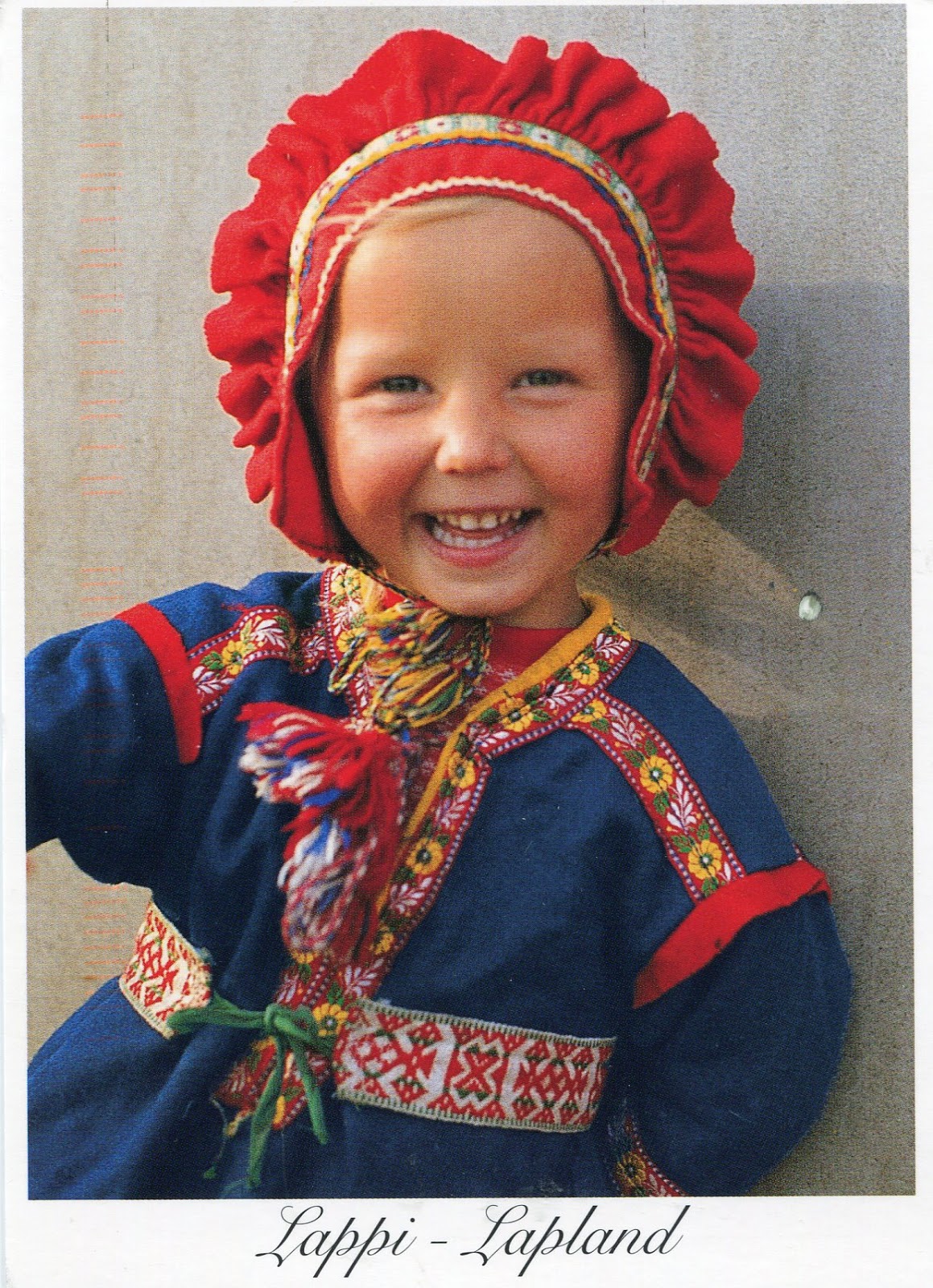

The Lapps

While the Sami, or Lapps, are commonly

thought of as the inhabitants of Lapland, they have never had a country

of their own. They are the original inhabitants of northern Scandinavia

and most of Finland. Their neighbors have called them Lapps, but they

prefer to be called

Samer

or

Sami

, since Lapp means a patch of cloth for mending and was a name imposed

on them by the people who settled on their lands. The Sami refer to

their land as

Sapmi

or

Same.

The Sami first appear in written history in the works of the Roman author Tacitus in about AD 98. Nearly 900 years later, a Norwegian chieftain visiting King Alfred the Great of England spoke of these reindeer herders, who were paying taxes to him in the form of furs, feathers, and whale bones. Over the centuries many armed nations—including the Karelians, Swedes, Danes, Finns, and Russians—demanded their loyalty and taxes. In some cases, the Sami had to pay taxes to two or three governments—as well as fines imposed by one country for paying taxes to another!

Today the Sami are citizens of the countries within whose borders they live, with full rights to education, social services, religious freedom, and participation in the political process. Norway, Sweden, and Finland all have Sami parliaments. At the same time, however, the Sami continue to preserve and defend their ethnic identity and traditional cultural values.

Traditionally, the Sami lived in a community of families called a siida , whose members cooperated in hunting, trapping, and fishing. Officially, the number of Sami is estimated at between 44,000 and 50,000 people. An estimated 30,000 to 35,000 live in Norway, 10,000 in Sweden, 3,000 to 4,000 in Finland, and 1,000 to 2,000 in Russia.

Sami is rich in words that describe reindeer, with words for different colors, sizes, antler spreads, and fur textures. Other words indicate how tame a reindeer is or how good it is at pulling sleds. There is actually a separate word describing a male reindeer in each year of his life. A poem by Nordic Council-prizewinning poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää consists mainly of different Sami words for different kinds of reindeer. There are also hundreds of words that differentiate snow according to its age, depth, density, and hardness. For example, terms exist for powdery snow, snow that fell yesterday, and snow that is soft underneath with a hard crust on top.

The Sami creation myth, directly related to their harsh environment, tells the story of a monstrous giant named Biegolmai, the Wind Man. In the beginning of time, Biegolmai created the Sapmi region by taking two huge shovels, one to whip up the wind and the other to drop such huge amounts of snow that no one could live there. One day, however, one of Biegolmai's shovels broke, the wind died down, and the Sami were able to enter Sapmi.

Some of the Sami epics trace Sami ancestry to the sun. In the mid-nineteenth century, a Sami minister, Anders Fjellner, recorded epic mythical poems in which the Daughter of the Sun favored the Sami and brought the reindeer to them. In a related myth, the Son of the Sun had three sons who became the ancestors of the Sami. At their deaths they became stars in the heavens, and can be seen today in the belt of the constellation Orion.

The Sami first appear in written history in the works of the Roman author Tacitus in about AD 98. Nearly 900 years later, a Norwegian chieftain visiting King Alfred the Great of England spoke of these reindeer herders, who were paying taxes to him in the form of furs, feathers, and whale bones. Over the centuries many armed nations—including the Karelians, Swedes, Danes, Finns, and Russians—demanded their loyalty and taxes. In some cases, the Sami had to pay taxes to two or three governments—as well as fines imposed by one country for paying taxes to another!

Today the Sami are citizens of the countries within whose borders they live, with full rights to education, social services, religious freedom, and participation in the political process. Norway, Sweden, and Finland all have Sami parliaments. At the same time, however, the Sami continue to preserve and defend their ethnic identity and traditional cultural values.

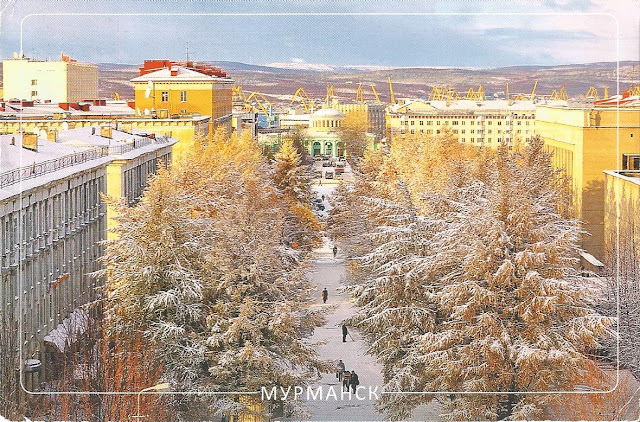

• LOCATION

The Sami live in tundra (arctic or subarctic treeless plain), taiga (subarctic forest), and coastal zones in the far north of Europe, spread out over four different countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia's Kola peninsula. They live on coasts and islands warmed by the Gulf Stream, on plateaus dotted by lakes and streams, and on forested mountains. Sami territory lies at latitudes above 62 degrees north, and much of it is above the Arctic Circle, with dark, cold winters and warm, light summers. It is often called the "land of the midnight sun" because depending on the latitude, the sun may be visible for up to seventy days and nights straight in the summer.Traditionally, the Sami lived in a community of families called a siida , whose members cooperated in hunting, trapping, and fishing. Officially, the number of Sami is estimated at between 44,000 and 50,000 people. An estimated 30,000 to 35,000 live in Norway, 10,000 in Sweden, 3,000 to 4,000 in Finland, and 1,000 to 2,000 in Russia.

• LANGUAGE

Sami is a Finno-Ugric language that is most closely related to Finnish, Estonian, Livonian, Votic, and several other little-known languages. While it varies from region to region, it does so based on the lifestyle of the Sami people rather than on the national boundaries of the lands in which they live. In fact, the present official definition of a Sami is primarily a linguistic one. Altogether there are fifty dialects, but these fall into three major groups (east, central, and south) which are unintelligible to one another, which is to say that speakers of one dialect sill not understand those of another dialect. Today almost all Sami also speak the language of their native country.Sami is rich in words that describe reindeer, with words for different colors, sizes, antler spreads, and fur textures. Other words indicate how tame a reindeer is or how good it is at pulling sleds. There is actually a separate word describing a male reindeer in each year of his life. A poem by Nordic Council-prizewinning poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää consists mainly of different Sami words for different kinds of reindeer. There are also hundreds of words that differentiate snow according to its age, depth, density, and hardness. For example, terms exist for powdery snow, snow that fell yesterday, and snow that is soft underneath with a hard crust on top.

4 • FOLKLORE

Traditionally, the Sami believed that specific spirits were associated with certain places and with the deceased. Many of their myths and legends concern the underworld. Others involve the Stallos, a race of troll-like giants who ate humans or sucked out their strength through an iron pipe. Many tales involve Sami outwitting the Stallos. Another kind of villian in Sami folklore is the stallu, a usually wicked person who can appear in various forms.The Sami creation myth, directly related to their harsh environment, tells the story of a monstrous giant named Biegolmai, the Wind Man. In the beginning of time, Biegolmai created the Sapmi region by taking two huge shovels, one to whip up the wind and the other to drop such huge amounts of snow that no one could live there. One day, however, one of Biegolmai's shovels broke, the wind died down, and the Sami were able to enter Sapmi.

Some of the Sami epics trace Sami ancestry to the sun. In the mid-nineteenth century, a Sami minister, Anders Fjellner, recorded epic mythical poems in which the Daughter of the Sun favored the Sami and brought the reindeer to them. In a related myth, the Son of the Sun had three sons who became the ancestors of the Sami. At their deaths they became stars in the heavens, and can be seen today in the belt of the constellation Orion.

Comments

Post a Comment